A long time ago, I saw the George Clooney remake of Solaris, a movie about which I remember essentially nothing except that I sort of hated it. The open (and unanswerable) question is: was past me wrong? Later, my horror(?) movie podcast decided to watch the original[1]

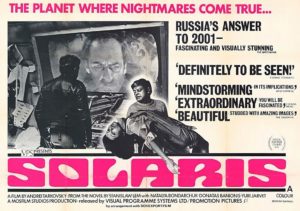

A long time ago, I saw the George Clooney remake of Solaris, a movie about which I remember essentially nothing except that I sort of hated it. The open (and unanswerable) question is: was past me wrong? Later, my horror(?) movie podcast decided to watch the original[1] Russian Soviet adaptation of the Stanislaw Lem novel, which is what brings us here today. Arguably, having watched these movies in reverse order, I should next pick up the book.

Solaris, in a non-spoilery nutshell: there’s this guy, and he wanders around his family property staring distantly at the lake and the underwater reeds and the empty road. Later, a second guy comes to visit and recap his history with the largely oceanic planet Solaris, which we[2] have a station in orbit around. Some people went missing, and the second guy piloted a failed solo rescue mission in which he saw a lot of weird things that his onboard camera system did not corroborate, as a result of which he has advice for the first guy, who is a psychologist going to the station to decide whether it should stay open. Also, the second guy has a son who seems unfamiliar with the concept of horses, and then afterwards the second guy and the son go on a long, pointless[3] drive in [probably] China. Later yet, the psychologist goes to the station, and discusses with the remaining two residents a) what happened to the until recently remaining third resident (who was the psychologists’s friend) and b) why there are in fact rather more than two residents. Then he spends the remainder of the movie coming to grips with the answers they provide him, as well as the answers they do not provide him.

I think I might have gotten more out of the film if I had a better grasp on the painting where those hunters(?) are returning to town on a ridge while everyone ice skates in the valley town below, or more fully caught the Tolstoy and Dostoevsky references, for examples. But even at three hours, it only wears out its welcome once or twice during the most drawn out and inexplicable scenes, or when director Tarkovsky gets a little too clever by switching to various black and white shades as though we’re meant to know what is being conveyed by this change in that moment. The rest of the time, we are presented with a slow (nay, lingering) meditation on what it means to be human, and to behave humanely, in the face of the unknown.

And really, you cannot ask for much more out of your science fiction than that.

[1] False! There was a TV movie in the USSR four years earlier, which, huh, okay.

[2] humanity? The Soviets? It’s not perfectly clear, but probably humanity.

[3] Okay, that’s editorializing. I have no idea whether it was in some way central to the plot or it wasn’t.